Lobsters: a case study in community management

Here we delve into local lobster fisheries, the Marine Protected Area Governance (MPAG) project, and how its founder, Peter Jones, is helping to create effective, sustainable interactions between people and the ocean.

For many people, lobsters are a delicious treat – but for many others they are a daily lifeline.

In the coastal community of Saint Luce in the Deep South of Madagascar, for example, fishing is the main source of income for four out of five people, and spiny lobster is the most lucrative target species. When we consider that 90% of people in the Deep South live below the $1.90 US dollars/day international poverty line, it starts to become clear just how critical the oceans are

But lobsters take a long time to reproduce and an even longer time to grow to their full size – while older fisherman talked of days when one man could bring back 20 kg of lobster in his boat, by 1990 their daily average haul had halved. By 2014 a fisherman counted himself lucky if he came back to shore at the end of the day with one kg of lobster on his boat.

Something needed to be done to stop the lobster populations diving off a cliff, and taking local livelihoods with them.

Community management

An international non-governmental organisation, SEED Madagascar, therefore launched Project Oratsimba to help Anosy and its surrounding area, Sainte Luce, manage their oceans in a sustainable way. These community-managed spaces, often called a locally managed marine area (LMMA), can benefit hugely from having on-the-ground local knowledge and buy-in, rather than relying on top-down governance approaches.

With SEED’s support the community was able to establish a Riaky (‘Sea’) Committee which introduced management measures through a dina (a customary system of law). Since 1996 these dina carry the force of law, and, once ratified, are enforceable by the Malagasy State.

To attempt to stop the lobster populations from diving even further, the Committee established 45 articles in their dina in addition to existing national legislation, including:

- banning fishing lobsters that are carrying eggs, or are smaller than 20cm

- A ‘no take zone’, where areas of the coast are periodically closed to allow populations to bounce back

- A fine for any infringement of up to about 28 American dollars, and one zebu (a cattle originally from South Asia, but very common in Madagascar)

After the first no take zone launched in 2014 there was a brief spike in the amount of lobsters caught per pot – and this even happened again in subsequent launches. This sudden increase in the numbers of lobsters over a short time period meant fishers could ask for higher prices from the merchants, as they competed for the bounty of lobsters (which also meant fishers were more likely to look more favourably on fishery management…).

These were short-term impacts, however, and wouldn’t lead to a real recovery of the local lobster populations. That would take sustained, long-term effort, and likely a whole suite of targeted management approaches.

Uncovering the barriers

So how could the LMMA be improved to achieve significant long-term impacts? What would make lobster populations bounce back? What would secure a sustainable future for the community and the ecosystem it relies on?

This is what Peter Jones, Reader in Environmental Governance at University College London, set out to discover. With a background in marine ecology, broadening into studies of policy and conflicts in Marine Protected Area (MPA) management, he has a long history of interest in understanding how MPAs actually, practically, work. What makes certain incentives effective? How do different political, social and biological factors affect the outcome? And how can we learn from them to create more effective MPAs in the future?

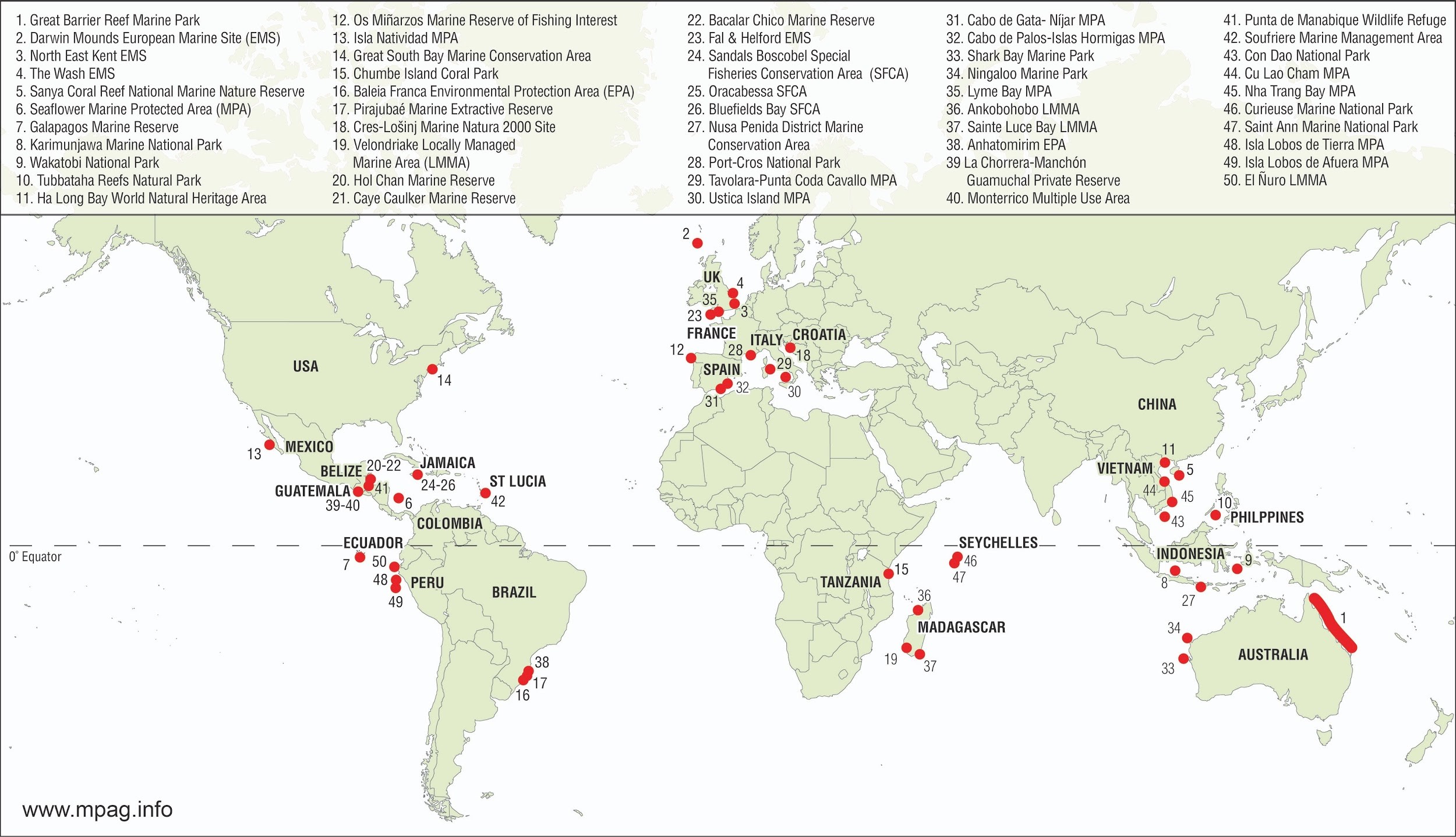

So in 2009 he launched the Marine Protected Area Governance (MPAG) project to analyse MPAs for their successes, weaknesses, and opportunities. It now holds 50 case studies!

While primarily focused on research ‘on the ground’, he and his team also incorporate an in-depth understanding of the political and legal situation as well as the behaviour and characteristics of the species involved, providing a deep, comprehensive review and suggestions.

He and his team started with identifying why there was still an unsustainable level of fishing in the first place. What they found can be broadly separated into three main issues:

- Poverty, and a lack of other livelihoods – some fishers simply couldn’t afford to obey all the regulations. It’s hard to ask someone who’s living below the poverty line to throw a lobster back in the ocean simply because it’s carrying eggs, or because it’s too small. And it’s not as if they have lots of other options: the surrounding land is very sandy and unsuitable for agriculture, there is also very little transport infrastructure, and a struggling education system leaves less than half of people over 15 years old able to read.

- Migration and population growth – those same fishermen who remembered boats hauling 20kg of lobster back on their boats also remembered there being about 20 fishers in Sainte Luce. Now, there are anywhere between 400 and 600. This is largely due to migration (being known as a hot-spot for lobsters is not always a good thing), but population growth also plays a part with women in some coastal areas having an average of six children.

- Enforcement – the two enforcement groups responsible for enforcement are sadly under-resourced. The Regional Fisheries Authority only have one or two agents but no operational patrol vessel or vehicle, while the Fisheries Surveillance Centre has a total of three boats to patrol a million km2 of ocean – an area about the size of Egypt.

It is often hoped that community-based management, such as this LMMA, can fill the gaps when there is little government funding. However, it is very difficult to enforce fines on people in your own community, and many people cannot afford to pay the full amount anyway.

Making it work

Essentially, Peter and his team found that the LMMA, and the dina it was trying to enforce, were not as effective as they could be because they didn’t adequately address the local drivers and because of a lack of back-up state enforcement capacity.

In a recent paper he and his team delve into the details, discussing the particular idiosyncrasies of the area that can make or break a LMMA. For example, when investigating whether tuna and sardines could play a larger role in people’s income they learnt a very practical problem – there are no ice facilities in the area and no established export route, so there is only limited demand from local markets and prices are low.

In a recent paper he and his team delve into the details, discussing the particular idiosyncrasies of the area that can make or break a LMMA. For example, when investigating whether tuna and sardines could play a larger role in people’s income they learnt a very practical problem – there are no ice facilities in the area and no established export route, so there is only limited demand from local markets and prices are low.

Other issues related to transparency in the Committee itself – it is meant to invest any fines back into managing the area, but there is little public explanation of where exactly the money goes. As well as leading to general distrust this also means people are much less likely to pay any fines they may incur. Having regular democratic elections to the Committee and a more transparent system of accountability was suggested as a solution.

Training people in other livelihoods has also been shown to help supplement people’s income, but not replace lobster fishing. SEED’s ‘Stitch’ project, for example, trained 21 women how to embroider, and there are now over 100 people selling their products to domestic and international markets – some of the men are even joining in. Those men are still fishing though, so it hasn’t effectively slowed the decline in the lobster fishing, though the income from selling embroidery products is approaching that from the lobster fishery.

Ultimately, Peter and his team found that an LMMA, or MPA, needs a number of different incentives to actually work. They developed a number of different types (economic, communication, knowledge, legal, and participation), and recommends that each governance structure has at least one incentive from each type. In this case there was a particular need for state assistance with enforcing the dina restrictions and penalising rule-breakers, coupled with a more transparent system of accountability on how the revenue raised from fines is being reinvested in the fishery and local community infrastructure e.g. repairing local roads and bridges.

Ultimately, Peter and his team found that an LMMA, or MPA, needs a number of different incentives to actually work. They developed a number of different types (economic, communication, knowledge, legal, and participation), and recommends that each governance structure has at least one incentive from each type. In this case there was a particular need for state assistance with enforcing the dina restrictions and penalising rule-breakers, coupled with a more transparent system of accountability on how the revenue raised from fines is being reinvested in the fishery and local community infrastructure e.g. repairing local roads and bridges.

This makes the governance more resilient, effective, and equitable – really addressing the core reasons of why the LMMA was established in the first place. When creating new LMMAs, it is key to consider what incentives will work, and what’s actually realistic, recognising that whilst community-based approaches are important, the supporting and enforcement back-up role of the state is also very important for promoting effectiveness and ensuring equity.

Impact

This approach to MPAG is already making waves – MPAG rationale and findings formed the basis of the governance stream of the international 10X20 Conference (7-9 March 2016, Rome) to support the achievement of a globally agreed target to conserve at least 10% of coastal and marine areas by 2020. This is part of the 10X20 initiative, organised by the Government of Italy, the United Nations Environment Programme and the Ocean Sanctuary Alliance. The first two days of the conference involved 25 international experts in discussions on good practice for measures to designate and promote the effectiveness of marine protected areas (MPAs), focusing on science, governance and finance.

More recently, the MPAG rationale and findings formed the basis of the opening presentation of the case studies session of a recent workshop (10-12 April 2018), organised by the Ministry of the Environment of Brazil and UN Environment. This is part of Brazil’s initiative to develop a white paper: Options for enhancing management of marine protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures. The MPAG presentation included some recommendations for this new national MPA strategy, which can be found in the slides of the MPAG presentation.

This MPAG research is also one of six highlights featured in UN Environment’s Frontiers 2017 report (pp.35-46) launched at the UN Environment Assembly 2018, Nairobi – “Ultimately, governing the oceans in a sustainable way could see Marine Protected Areas as a driver – not a limit – for the vital economic and social benefits that we derive from the global ocean”. This highlights a forthcoming UN Environment output based on an analysis of 34 case studies: Enabling Effective and Equitable Marine Protected Areas: guidance on combining governance approaches (will be available soon here).

Ultimately, taking this in-depth, comprehensive and interdisciplinary approach to marine management presents huge opportunities for sustainable solutions.